OMA

How OMA applies generative design capabilities to complex design challenges

CUSTOMER STORY

Share this story

Summary

Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), the Rotterdam-based architecture firm founded by Rem Koolhaas, is the creative force behind some of the world’s most iconic buildings, including France’s Maison à Bordeaux and Milan’s Fondazione Prada. The firm’s partners are skilled at leveraging bleeding-edge technologies like BIM, computational design, automation, and generative design to explore and optimize design choices—as they did with the design of Rotterdam’s new Feyenoord Stadium. The stadium will be home to the Feyenoord Football Club and is part of a wider Feyenoord City master plan, which includes urban development of the nearby Rotterdam-Zuid neighborhood.

“Since the stadium typology challenged us, the generative design helped us explore resolutions for some of our unique design challenges.”

—Alex Mortiboys, Head of BIM and Design Technology

Photo courtesy of OMA.

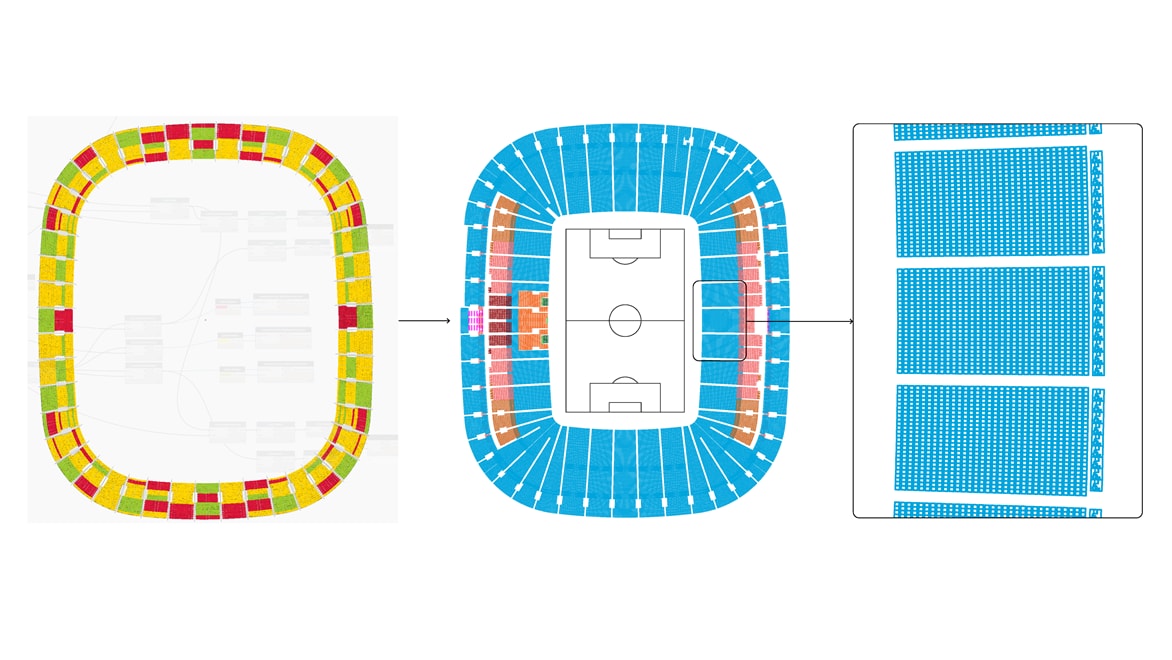

A quality viewing experience from every seat

The OMA team worked with engineers Royal HaskoningDHV (RHDHV) on the overall stadium design, with RHDHV delivering the structural design and OMA defining the diagrid form, including the façade as well as the layout for the stadium’s 63,000 seats. The OMA design team wanted to optimize the stadium’s facade design for both constructability and cost, as well as explore opportunities for adding additional seats to the stadium without sacrificing C-values, or spectator sightlines, to offer fans the best views from every seat.

The generative design process involved new ways of thinking about design, as well as software tools. Project Refinery, Autodesk’s generative design beta, which has migrated to Generative Design in Revit, helped OMA iterate on designs to find the highest-performing option within their design constraints. To help the design team adopt a generative design approach, Giuseppe Dotto, Computational Design Specialist for OMA, joined the stadium design team to help architects understand the questions to pose during the generative design workflow.

Iterative workflows for better outcomes

“We’d created the seating placement using computational design, but we hadn’t interrogated the efficiency of the layout,” Mortiboys explains. “This was the high-pressure moment of the project—using Project Refinery* and Dynamo to see if we could add more seats as close to the pitch as possible while optimizing spectators’ visibility, or C-Value.”

With iterative workflows, the OMA design team rapidly tested and optimized seating designs that would meet the required compromise between the number of seats and the desired C-values—using project limits as defined by the architects. “Defining the boundaries gives you a starting point for testing,” Mortiboys explains. “At that point, it was down to geometry—examining the pitch of the seats or changing vertices and seat widths to find the best compromise.”

Generative design studies

The OMA design team also used generative design to study options for the stadium’s proposed undulating metal facade. The metal forms were intended to be triangulated; the design team sought options for reducing design variations in order to improve constructability and reduce construction costs.

“I think of generative design as another member of the team that helps us get resolutions for better use of the resources we have,” Mortiboys says.

* Project Refinery is now Generative Design in Revit

“I think of generative design as another member of the team that helps us get resolutions for better use of the resources we have.”

— Alex Mortiboys, Head of BIM and Design Technology

Photo courtesy of OMA.

Using resources efficiently to generate design options

By iterating designs, the team was able to add an additional 600 seats to the stadium while maintaining the desired C-values, and refine new ideas for the stadium’s facade.

“The benefits of using generative design in the project were twofold,” Mortiboys explains. “Not only does it enhance efficiency thanks to the speed of the AI-powered design process, but it also goes into much more granular detail within the constraints for many more iterations than we would have previously. That means we could generate hundreds of designs based on our requirements quickly and easily.”

“Looking beyond stadiums, we can see generative design's application to analyze and inform form, construction, sustainability, and the complex factors that underpin a design response's socio-economic intention.”

—David Gianotten, Managing Partner, OMA

Photo courtesy of OMA.

Investigating generative design applications

The value that generative design brought to the project has inspired the OMA team to apply the process to future OMA projects, regardless of scale. “My aspiration is that we’ll have generative design as part of every project—from an early-phase master plan through to highly technical questions like improving a seating layout,” Mortiboys says. “I’d like generative design to become a day-to-day tool that’s part of everyone’s skill sets.”

Mortiboys also envisions the tremendous potential for generative design’s creative and efficient workflows to help OMA’s architects rapidly address the pressing needs of the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry to design for population growth and sustainability.

Using generative design to solve for the challenges that matter

“The built environment, which contributes 39% to the world’s carbon footprint, has a responsibility to take on these issues,” he says. “If we have tools that will help us understand how we can better use the resources we have, then we should use these tools to create designs that are better for the planet.”

“To paraphrase Buckminster Fuller, we now have systems like generative design that help us do more and more with less and less—and let every member of the team test and refine their creative ideas,” adds Mortiboys. “The possibilities for using design as a tool for driving global change have never been more exciting.”

Driving towards design outcomes

OMA Managing Partner David Gianotten agrees, “Generative designs' use in Feyenoord Stadium parallels our ongoing research into the technology's application across other segments of our practice. This tool aligns with our belief; our outcomes must remain informed by research, data, and analysis, where innovation is the driver to solve our design briefs.”

“Looking beyond stadiums, we can see generative design's application to analyze and inform form, construction, sustainability, and the complex factors that underpin a design response's socio-economic intention”, Gianotten says. “Given the converging issues that the built environment will face in the coming years, it is exciting to envision how we will utilize generative design to engage with these challenges.”